Navigating Norman Creek: Maps from 1839 and 2015

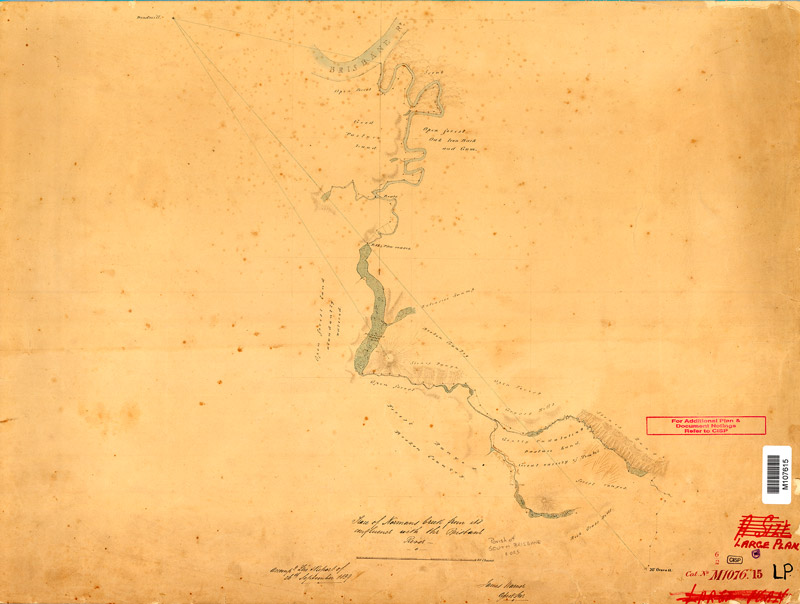

Following John Oxley’s surveys of the Brisbane River and its environs in 1823 and 1824, the city of Brisbane began as a penal colony, established initially at Redcliffe in 1824 and moved to the site of the present CBD in 1825. Only when the penal colony started to wind down in 1839 did the colonial government survey the surrounding lands with a view to creating a free settlement, with the Norman Creek catchment among the first areas to be surveyed. James Warner, a government surveyor, produced the plan shown below in September 1839. Warner surveyed the entire length of Norman creek, from its headwaters in Mount Gravatt to its confluence with the Brisbane River. His survey focused on the state of the vegetation, water, soil and topography of the land, all with a view to assessing its potential for further development. The original document spans 62cm x 52cm and is held in the Queensland Museum of Lands, Mapping and Surveying.

Warner’s plan not only captures every nook and cranny of the stream, but also includes sketches and annotations describing the surrounding vegetation and terrain, as exemplified in the detailed section shown below.

This detailed section shows the creek as it flows through Holland Park West, but it’s hard to know this by looking at the plan alone. With the help of modern mapping technologies, we can superimpose and compare maps from different eras to see more easily how things have changed. The images in the remainder of this page show features from Warner’s plan superimposed on the current landscape as viewed in Google Earth. The details from Warner’s plan have been widened and recoloured in these images to make them more visible against the current landscape. You can hide or reveal these details by moving the image slider to the left and right.

When viewing these images, be aware that the alignment of Warner’s plan with the modern landscape is only approximate. This is because there are very few reference points that appear in both Warner’s plan and the modern landscape. The only human-made feature on Warner’s plan is the old windmill at Spring Hill, which remains today as Brisbane’s oldest building. Meanwhile, the path of Norman Creek has been altered significantly by human activities, and may have changed naturally in some places as well. Thankfully, other resources exist, such as the 1946 aerial imagery of Brisbane, which show the creek in a less modified state than today, providing the missing link between Warner’s plan and the current landscape.

The first image below shows the full extent of Warner’s plan overlaid on the suburbs of today. Moving the image slider will reveal the boundary of the Norman Creek Catchment in blue, and some details of Warner’s plan in yellow. Also revealed are the names of various natural landmarks, both modern and historic.

The next image provides a closer look at the south-eastern part of the plan, which includes parts of Holland Park and Mount Gravatt. The branch of the headwaters known today as Ekibin Creek is depicted as a wide and/or swampy stream flowing beside Nursery Road and then along the path of the Pacific Motorway and South-Eastern Busway. Written across the motorway (though hard to read in this image) are the words ‘Tea tree’, presumably indicating that melalucas or leptospermums once grew in this part of the creek. The hill depicted towards the bottom of this image appears to have been partly levelled to accommodate the playing field of Holland Park State High School. Also depicted on this image is the stream known today as Glindemann Creek running through what is now the Mount Gravatt Homemaker Centre and Glindemann Park.

Between these two streams, Warner’s annotations indicate gently undulating pasture land with a great variety of timber, as shown in the image below. To the east Warner saw a stony range, while to the north he found grassy hills.

The next image shows where Ekibin and Glindemann creeks meet to form the main stream of Norman Creek, which flows here between the motorway and Greenslopes Hospital (today the Greenslopes DCP site) to Arnwood Place. The path of the creek as mapped by Warner is quite similar to that of the modern creek. Interestingly however, Warner has not traced the path of Sandy Creek, which flows through Tarragindi to meet Norman Creek at Arnwood Place. Perhaps 1839 was a dry year with that tributary little in evidence. Or perhaps Warner saw limited potential in the surrounding land. Rather unflatteringly, he described the forest ranges of Tarragindi as ‘broken country’.

On the northern side of Arnwood Place Warner sketched Stephens Mountain and a stoney range, while to the south he observed an open forest. The straight line emmanating from Stephens Mountain (along with the line emmanating from Mount Gravatt) in these images can be traced all the way to the old windmill in Spring Hill. These are evidence of the surveyor’s craft and its dependence on imaginary lines from the highest points of land. Earlier in 1839, prior to surveying Norman Creek, Warner had cleared the top of what we now know as Mt Coot-tha and established the first Brisbane trig point to assist in his future surveying endeavours.

Upstream (northwards) from Arnwood Place, Warner found a large swampy area with permanent water holes. This area would later become known as Burnetts Swamp, and is today the long strip of parkland incorporating Ekibin Park, Thomson Estate Reserve, AJ Jones Recreational Reserve and Hanlon Park. Comparing Warner’s map with the contemporary Google Earth images demonstrates how much the path of the creek has been tamed and shifted to accommodate sporting fields, sewerage and storm water and the South East Freeway. At the bottom of the image above is where T B Stephens had his wool scouring business, using the water from the creek to wash lanolin and dirt from wool, for several decades in the mid nineteenth century.

At the top of Burnett’s swamp, Warner marked the point at which the ebb and flow of the tide ceased. Hovering over the image below reveals that this point was only a short distance upstream from the bridge on Logan Road (leading into O’Keefe Street), which is approximately where the tidal flow ceases today. Just upstream of the Buranda State School playing field, Warner showed a hairpin bend in the creek that has since been bypassed and built over. Further upstream (at the top of the image below), Warner’s plan depicts the old creek winding around Moorhen Flats and being joined by a tributary which has since been built over.

The next image shows Moorhen Flats more clearly, and reveals the original meandering path of the creek thorugh East Brisbane and Coorparoo (the original path can also be seen in the 1946 aerial images). Most of this straightening out of meanders was undertaken by the Brisbane City Council between the late 1980s and early 1990s. An intriguing feature on this image is Warner’s annotation of ‘Boats’ near Moorhen Flats. Whether this refers to boats used by Aboriginal people or of the settlers associated with the Moreton Bay convict settlement is not known.

Finally, the image below shows that in the lowest reaches of the creek, the path has changed little since Warner surveyed it in 1839. Long gone, however, is the open forest of oak (presumably casurina species), iron bark and gum.

Composite images by Angus Veitch. Text by Angus Veitch and Trish FitzSimons.

For further information:

W. S. Kitson, ‘Warner, James (1814–1891)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed online 5 December 2015.

Janet Spillman, 2010, Looking at Mount Coot-tha, Queensland Historical Atlas.